CONFLICT MINERALS AND FAILED REGULATION TOWARDS A REVISION

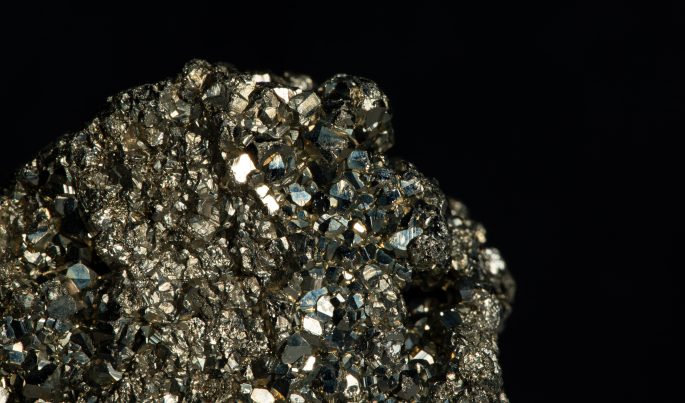

February 8, 2022Anyone who has visited a mining area in Africa must have been struck by the negative impact of the activities of extractive companies. These include the complete change of the landscape, the displacement of populations, the local roads destroyed by heavy trucks and mountains of mineral waste. Then there are the comings and goings of people attracted by the crumbs that mining com-panies leave behind. Crowds of people (including children) scavenge for scraps of minerals among the excavated rocks that are discarded for their low yield, but which provide them with means to earn some money.

These scavengers, as well as artisanal miners, make a living selling what they find on irregular mineral markets. If these activities are carried out in conflict-affected and high-risk areas, the economic benefits often end up in the hands of armed groups. To prevent the profits of buying and selling minerals ending up in the hands of rebel and armed groups, the European Union adopted a directive, the European Conflict Minerals Regulation, that entered into force on January 1, 2017. This Regulation required mineral importing companies of the European Union (EU) to trace minerals throughout the supply chain of their providers. Companies that purchased minerals from smelters and refiners that had bought the minerals from armed groups would be subject to sanctions.

Ineffectiveness of the directive

As with other legal provisions, the business lobby missed no opportunity to water down the content of the Conflict Minerals Regulation (CMR). First, the mining companies succeeded in making the directive transitional. The directive was initially implemented as a voluntary regulation in 2017 and only became mandatory in January 2021. Even then, the situation did not change in the places where rebel groups controlled mining areas. In 2020, 44% of investigated companies could not finally report on mineral origins.

The laxity of companies in their implementing of the directive requires the EU to give greater attention to the control of its multinationals and to establish consistent measures in the implementation of the directive.

The CMR was unwillingly, and so inadequately, drafted by the EU. Its scope was limited to particular minerals, such as tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold, and excluded others of equal relevance for new technologies, such as cobalt and nickel. As well, in recent years, the EU has developed new needs for rare metals used in energy pro-duction through renewable energies, such as lithium, indium, lanthanum, yttrium and europium. The revision of the CMR planned for 2023 must include all rare minerals and metals essential for developing a green economy.

Accompanying measures

The directive requires accompanying measures to enforce the ban on imports of minerals that finance armed groups in conflict-affected and high-risk areas. Member States do not agree on these measures and offer varying and undemanding responses to infringements of the Regulation.

Most EU countries consider that companies importing minerals from conflict zones that do not comply with the directive should incur a financial penalty; others, such as Finland and France, support the idea of banning imports from such companies for a set period of time, ranging from one month to one year. Other countries, such as The Netherlands, Sweden and the Czech Republic propose making public the names of offending companies to persuade them to comply with the law.

The revised directive must include penalty mechanisms that ensure coherent action and prevent States from reducing the effectiveness of the Regulation. EU solidarity, so often touted by the EU, should start with something as basic as supporting African States in their fight against the terrorism of armed rebel groups and human rights violations.

Source: José Luis Gutiérrez Aranda, Corporate Justice,| Sept. 6, 2021, Africa Europe Faith and Justice Network (AEFJN). Edited Alison Healey.